Borrowed self

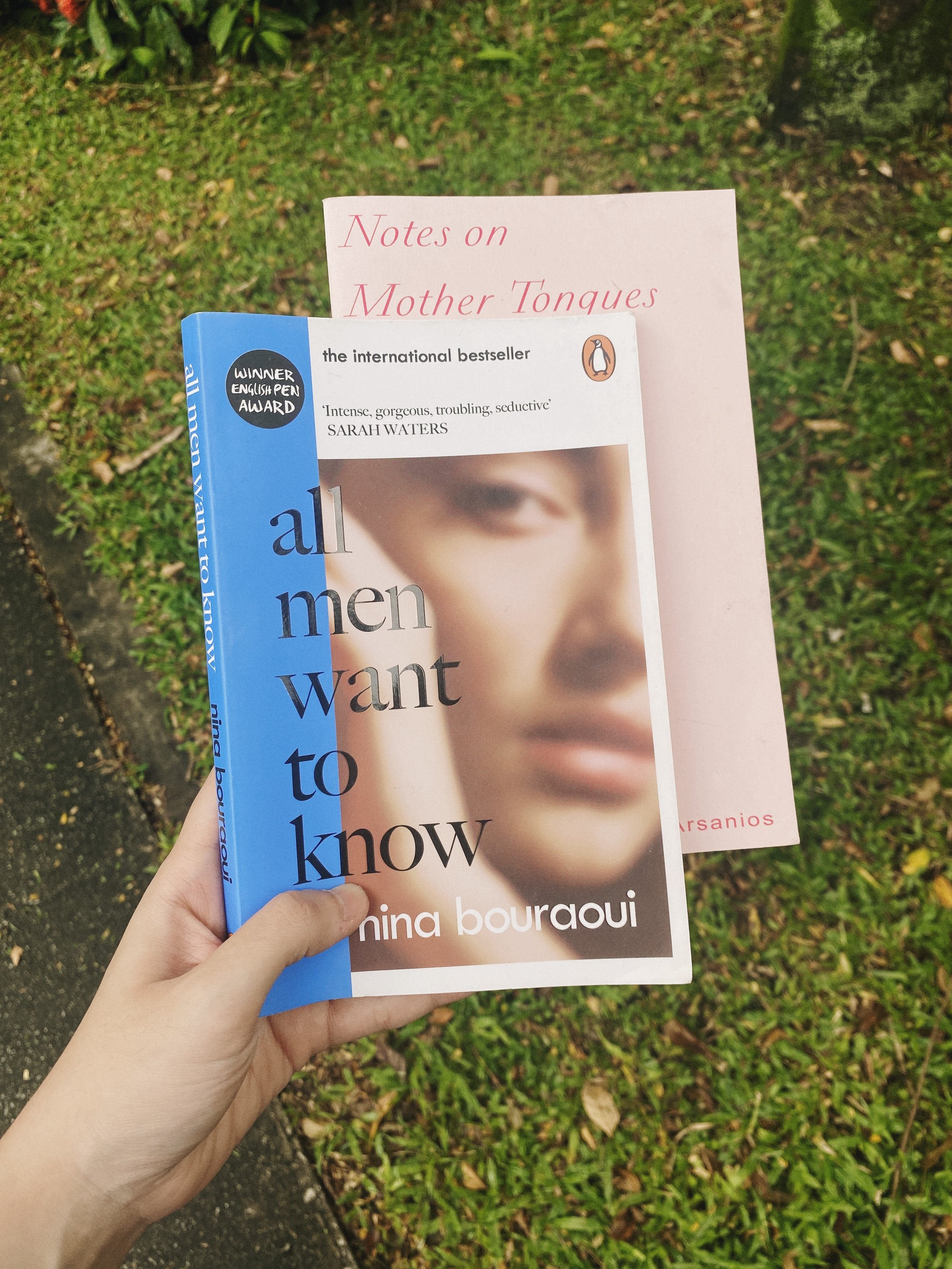

on Notes on Mother Tongues by Mirene Arsanios and All Men Want to Know by Nina Bouraoui

Where do I start? I picked up Mirene Arsanios’ pamphlet “Notes on Mother Tongues: Colonialism, class, and giving what you don’t have” with much joy, knowing I’ll find in her pages ideas of a liminal identity; the compromises, failings and invention of a self pinned between nations and cultures, hoping to find a language independent and pure. A child of Lebanon and Venezuela, Arsanios speaks a language that belongs to no one. She carries the coloniser’s tongue (French), yet it is only a transplant, and she goes in and out of rejection, separating the language from the self, yet finding only the self accountable for this makeshift language. The “I” (self) finds its way in between her passages while she speaks of her language in the third person, though more often she uses “My language” to refer to the “I” (“My language speaks of her countries in statistical and geopolitical terms because she wants to talk about love,”; “My language is engaged in the necessary but difficult enterprise of developing a language through which she can diagnose “herself” as a symptom of history”.). She finds both fusion and separation necessary: “knowing my language intimately means accepting the inherent split that exists between us, a dialectic of embodiment and estrangement that defines our relationship.” Between tongues, Arsanios surveys loyalty, otherness, love and decay as repercussions of colonialism. She wields a language that is motherless, fostered by poetry and traces of foreign tongues. Arsanios’ words bring me comfort.

Then, on an unplanned trip to Littered with Books, Arsanios’ pamphlet still in my backpack, I found on LB’s Quick Read Tree Nina Bouraoui’s “All Men Want to Know”, an autofiction that details her youth between the land and blood of her father, Algeria, and that of her mother, France. I knew instantly that Bouraoui must share Arsanios’ spirit. Two women, a world apart, sharing a borrowed language. Bouraoui wanders through an idealised Algiers she knew in her childhood, a memory smeared by a violent attack against her mother that forced her family to flee. She takes us afterwards to Paris, where she explored her sexuality, the borders of desire and violence, and learned the wonders and costs of freedom. Both places are written between three consciousness: remembering, knowing, becoming. Like Arsanios, Bouraoui is in search of a self free from the bindings of colonialism, and like Arsanios, she finds it could not exist. Confronting her rose-tinted memories of Algeria, Bouraui writes:

“my Algeria it’s a place of poetry, beyond reality. I’ve never been able to write about the massacres. I’m not entitled to, I can’t, I’m the Frenchwoman’s daughter.”

I find traces of Arsanios once more as Bouraui describes a feeling of separation, an inescapable isolation from either side of her cultures and history. It doesn’t work, Bouraoui writes: “it makes me uncomfortable, as if I’m outside my real self, as if I failed to love my whole self.” Both women feel deeply the displacement borne out of a liminal existence, the tender feeling of alienation that follows one through every phase of life. Yet, both women hold firmly to the joys of their solitude, a currency that has afforded them space from their immediate world, at once an opening to other worlds. As Arsanios offers “When I can’t find the words my language is looking for, we both pause and observe the gaps between our many languages, doors fleetingly open for the dead to return,” Bouraui writes

“I feel so small, a tiny speck in my bed, in the city, this country, this continent. I’ve cast off my bindings, I no longer have a name, I’m ageless, homeless, with no past, no family; all I have is a future, a future that will plunge me into another life.”

Bouraoui’s exploration of a mixed heritage identity moves me to no end. I feel, in reading her work alongside Arsanios’, that I am again challenged to see beyond generational trauma: when one carries the coloniser’s blood and traces of their language, mustn’t one give equal thought to generational consequence and responsibility? I read once that you could only strip yourself of the responsibilities of your ancestors if you no longer reap the privileges they have passed onto you. But the material – wealth, name, language, even whiteness – might survive through centuries, and to that end one bears the responsibility to investigate the self as both victim and perpetrator. I find higher sense now in Arsanios’ reference to the I as language: like language the self must be thought, interrogated, and at last spoken, to materialise and to endure.

Reading these women to end my year, I feel I am in good company once more, ambling sideways, between imperfect histories and disjointed kinship, finding my way to the self.